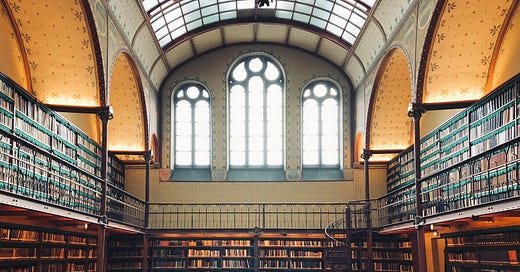

Photo Credit: Unsplash

One of the surprising things to me about going into the classroom has been how much I have enjoyed reading classic works again—and in many cases for the first time. I say “for the first time” because like many high school students I opted for Cliff’s Notes. I loved writing, but didn’t understand why we were reading Canterbury Tales or had to memorize passages in Middle English. Shakespeare fell flat when I read it, unless I was actually performing it. Even then, I needed someone to give me a summary first. Literature didn’t start capturing my interest until late into my senior year, which is why I continued with English all the way through college.

This year, I taught Beowulf in the first nine weeks. When I saw it listed in my curriculum guide, my heart sank. I hated Beowulf in school. I thought for sure my students would hate it—they mostly did. But I surprisingly didn’t. Once I did the background work to understand the context, the translation differences, and even the characters, I was intrigued. Karen Swallow Prior’s work on Beowulf also helped.

But the thing that struck me as we read together is how the themes in Beowulf are the ones we find in our modern stories. Beowulf is the great hero who comes to defend the vulnerable people against a ruthless monster, Grendel. He evades death many times, before finally succumbing to a dragon in his old age. Dying alone, he is defended by his loyal friend Wiglaf. In his death, he is celebrated and mourned according to the customs of his culture.

Like many, I watched the funeral of Queen Elizabeth. I will watch the funeral services and celebrations for former President Carter. I’m always down for a Marvel movie marathon. And I can get into the rabbit hole threads about what made Elphaba bad in Wicked—is she truly wicked or did she become wicked over time?

Beowulf asks all those questions. In fact, most of our classic literature does as well. Questions like:

Who would you die for?

Who is a hero to you?

What is a mark of bravery?

We asked those questions in class, and many more. When Grendel’s mother avenges her son’s death, we asked “what makes a mother respond with such murderous rage?” When Grendel peers into the mead hall, seeing a crowd of men enjoying companionship and swapping battle stories, always the outsider, we asked “are we responsible for our choices, even if we are responding in hurt or anger?” We even asked how our own interpretations of society impact how a work gets passed down over time. Do things get lost or added in translation?

The themes Beowulf draws out are ones we can relate to, if we listen for them. They’re imbedded deep in our own souls. They’re the reason we’re drawn to hero stories—like Superman and the Marvel series. They’re the reason we’re captivated by origin stories that explain the outcome of character’s lives—even ones that wind up the villain (like Wicked).

Tim Keller calls this a “memory trace.” As image bearers of God, there are memories in our soul that have been passed down from our first parents. Every generation has longed for a hero, sought to be loyal, and pondered the meaning of evil. If we look close enough, the heart motivations haven’t changed. We’ve just used different mediums. The ancients used oral stories passed down—we use CGI generated characters. But we all long for a hero. We all want to make sense of our stories. We all want to be understood and have someone fight for us.

This came up again when we read The Importance of Being Earnest, which also at first glance sounds super boring to a teenager. But in Earnest, you see an author’s critique of society—one that expects too much of people, leading them to choose a double life rather than be themselves. In some circles we call this codeswitching. But for the Christian, we also see how failing to honor the image of God in a person—in the myriads of ways it’s expressed—leads people either to a life of loneliness or make believe. The Christian story makes sense of all our stories.

For the teacher (who also happens to be a Christian), we know that if they don’t learn to understand the value of stories and trace the memories in their souls, they won’t be able to read it in the pages of scripture either. This is the building blocks of literacy. I believe strongly in biblical literacy, but if we don’t understand how to trace an ancient story in the classroom, we will struggle to trace it in a pew too.

You can’t get deeply into all of this in a public school classroom, but that’s okay. It still matters to help students see that our stories endure. The ones they tell now will be told again hundreds of years from now. What resonates in their souls are echoes from Eden, repackaged for our modern day. It helps them see that human nature is largely the same, which maybe comforts them a little when human nature leads to devastating consequences. Life is painful, our stories are marked with brokenness, but somehow, we endure. Maybe they will too.